While critics encourage better design and community activists lobby for responsible development, many times the compromises yield bland results or stagnant progress. In a culture once ruled by the commercial media, an explosion of personal technologies has given everyone an immediate voice.

Blogs rival traditional news sources with opinionated diatribes. Activists protest multiple causes from their iPhones. The audience is overstimulated with what ultimately amounts to little more than white noise. These technologies aren't bad, we just haven't learned how to deal with them yet.

Operating under antiquated expectations (and by antiquated, I mean the world before the web), City Council receives arguments presented by critics and activists as if they were an angry mob standing outside City Hall in 1980.

The rules of campaigning tell politicians that these loud voices are all potential votes, but these rules haven't compensated for the white noise and the internet mayhem. Essentially, politicians haven't figured out that most of today's vocal opposition isn't as dedicated as the picketers in the last century.

One day they're protesting billboards on Market East, the next they're blogging against horse-drawn carriages in Society Hill, and the next week they're at a Prop 8 rally in California. We have it so good we'll protest anything, and our elected officials need to know how to weed out the legitimate constituents from the hot air.

Willis Hale's macabre Lorraine Hotel, known now as the Divine Lorraine, has captured the imagination of each passerby for a century.

Willis Hale's macabre Lorraine Hotel, known now as the Divine Lorraine, has captured the imagination of each passerby for a century.

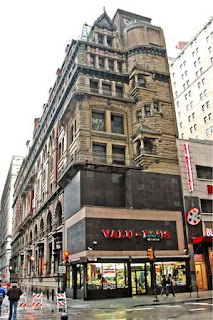

Frank Furness challenged conventional Victorian style with exaggerated elements and colors. Shown here is the National Bank of the Republic on Chestnut Street.

Frank Furness challenged conventional Victorian style with exaggerated elements and colors. Shown here is the National Bank of the Republic on Chestnut Street.

At a time when Philadelphia's skyline was dominated by City Hall and church steeples and New York's by Art Deco spires, the PSFS Building changed the face of urban American cities.

At a time when Philadelphia's skyline was dominated by City Hall and church steeples and New York's by Art Deco spires, the PSFS Building changed the face of urban American cities.

In what would seem like a complete disregard for the quaint Colonialism of Society Hill, I.M. Pei's towers gently compliment the surrounding brick row homes and parks. The towers were part of a massive, mid-century plan that turned the worst slums in Center City into some of the regions most desirable addresses.

In what would seem like a complete disregard for the quaint Colonialism of Society Hill, I.M. Pei's towers gently compliment the surrounding brick row homes and parks. The towers were part of a massive, mid-century plan that turned the worst slums in Center City into some of the regions most desirable addresses.

Focus groups lead to boring, formulaic television programs, and the same goes for art and design. Renderings are shopped around the newspapers, blogosphere, and community meetings, shuffled through several self-proclaimed "expert" organizations, and sent back to the drawing board to be stripped of all character.

While our voices are often important, we don't know better than the professionals. Sometimes those with a vision need to stand their ground and shock us.

Although Frank Furness is a household name to most Philadelphians, one of the most creative architects of the Victorian Era may also be one of the most underappreciated. Only vaguely adhering to the rigorous design requirements of his time, his deserved recognition is often lost in the history books, often with only a brief mention.

Although Frank Furness is a household name to most Philadelphians, one of the most creative architects of the Victorian Era may also be one of the most underappreciated. Only vaguely adhering to the rigorous design requirements of his time, his deserved recognition is often lost in the history books, often with only a brief mention.