I've lived across the street from the historic Big Brother Big Sisters building for about eight years now, and I've watched anti-developers bulldoze building after building, and I really thought that the BBBS building would be next. Aside from the grandiose buildings demolished for the Convention Center's expansion, most of the damage has been in the way of abandoned, one-story warehouses - no great loss - but typically replaced by more surface parking.

If you think the Gallery was a bad idea, just walk up to 13th and Vine.

As drab as it looks in renderings, Marriott's AC Hotel capping to the BBBS building is a welcome addition to my neighborhood.

Within the last few weeks, another old warehouse bit the dust. Unfortunately, a very cute apartment building went with it, and as far as I know, there are no plans for the site but more parking, apparent in the fact that the rubble was paved over in a day. It's amazing how long it takes for a potentially iconic piece of architecture to receive approval, yet how fast and inconspicuously another can be flattened.

The problem with this area is one that enables itself. Surface lot owners are lowly taxed and make bank off their lack of overhead. They occasionally pay for a minimum wage parking attendant, and barely maintain the asphalt. The rest is profit. The only time something gets developed around here is when something else gets torn down.

I've seen single buildings razed for no more than three parking spaces. The demolition is justified as a way to "clear the land" for speculative development, but if the property ever goes on the market, it goes on the market for twice its value because the profit margin on surface parking is so high. It's literally cheaper to demolish a building in this neighborhood and start from scratch than it is to build on a "cleared lot" advertised as "developable land."

What's most unnerving is how the cycle perpetuates itself. Surface parking on its own isn't a demand, but parking always will be, garaged or otherwise, because people are friggin' lazy. But surface parking scars the urban landscape and makes it undesirable for development. Over time, as surface parking grows, the reason to park there disappears.

My hometown of Harrisonburg, VA learned the hard way. With two large garages perfectly situated north and west, "downtown" was primed for a renaissance in the 1980s. People - the laziest people - didn't like walking two blocks, and parking "development" inched closer and closer to Court Square until every reason to ever go downtown was demolished. Twenty years later, and in a city with 1.5M more residents, I find myself living in the the middle of the exact same situation.

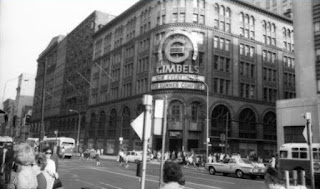

There isn't a single block of Center City real estate that doesn't have surface parking on it, yet we continue to allow it to chip away at our urban fabric. Had the historic Gimbels Department Store not been demolished for speculative development, it's hard to imagine real estate so close to City Hall would be so hard to unload. Even abandoned, that handsome piece of architecture would put more feet on to the cement than the Disney Hole provides in parking.

|

| I'd rather walk by this - abandoned - than another surface lot. |

My neighborhood - roughly bound by Broad, 11th, Market, and Vine - was Ground Zero for decades of civic redevelopment projects. Boxed in by the Pennsylvania Convention Center, the Vine Street Expressway, Market East Station, and the Gallery, it's become the bilge water for the city's bad ideas. The Convention Center has finally proven itself great for the region, but that isn't so great for its neighbors.

While City Planners and NIMBYs continued to argue over minute details elsewhere, an entire neighborhood has been almost exterminated.

I wish we still sidled up to some of the lofty warehouses that were here before the first leg of the PCC. If we were ever a part of Callowhill, that was the time. As it stands, we should be an extension of the Loft District, but Callowhill's neighborhood organization wants nothing to do with us. Who can blame them? Fighting surface lots is a Sisyphean task. At best we're under the PCDC, not the most progressive group.

But we are a neighborhood and a place Philadelphians call home. Marriott's AC Hotel might not bring more residents, but it adds to our sense of purpose. Our most impressive addition in the last twenty years has been the Hampton Inn, and while it's far from the best, its guests helped open the QQ Mart, run by one of the sweetest families you'll ever meet.

Philadelphia is doing great right now. It's hard to look at projects at 19th and Chestnut or 12th and Walnut without asking, "shouldn't we expect more?" But up at 13th and Vine - shoehorned between a highway and a massive project that should have come with its own parking - we don't have that luxury. We're begging for the developmental and architectural scraps, all in the hopes that it may someday bring more people, and eventually something better. The fact that anyone is talking about Marriott's AC Hotel means this lost corner of Center City - a corner a few blocks from City Hall - is relevant once again.

I have one of the best views of the city from my third floor bedroom window: the skyline atop the historic Big Brothers Big Sisters buildings. But despite my view and comparatively cheap rent, I'd trade it in a second for foot traffic and a brick wall filled with neighbors.