Following the second World War, urban planners like Philadelphia's Edmund Bacon were attempting to change the way Americans interacted with their city landscapes.

Following the second World War, urban planners like Philadelphia's Edmund Bacon were attempting to change the way Americans interacted with their city landscapes.Being responsible for The Gallery at Market East, Penn Center and the removal of the Chinese Wall, Society Hill, and the Vine Street Expressway, his projects were hit or miss.

He proposed a number of other controversial endeavors which, as his career progressed, seemed to become more destructive, including an additional expressway on South Street creating a downtown loop. Even though the man once suggested demolishing all but City Hall's clock tower to ease traffic around Penn Square, not all of his projects were aimed at turning Center City into an asphalt labyrinth of freeways and interchanges.

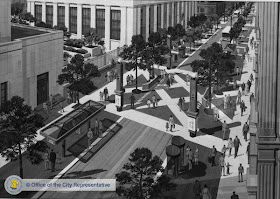

The Chestnut Street Transway was intended to reconfigure Center City's Chestnut Street into a trolley bound, pedestrian promenade. In 1959 Ed Bacon published "Philadelphia in the Year 2009," an essay proposing a number of his ideas, including many that have already been executed.

While his quasi futuristic ideas were aimed at preparing Philadelphia for a 1976 World's Fair that never arrived, his Transway did...sort of. In 1976, Chestnut Street was closed to traffic between 8th Street and 18th Street to develop what was being called The Chestnut Street Transitway.

Immediately after construction began Chestnut Street began to decline. A bustling retail corridor well into the 1970s, upscale shops began closing, moving to Walnut Street, or leaving the city all together.

Like a mall, the Transitway took life from the street. Councilman DiCiccio pointed out the importance of window shopping and the similarity between the Transitway and The Gallery, "we killed a major artery...window shopping is always important and we took that away."

The irony of course is that Chestnut Street was negatively impacted by a pedestrianization scheme intended to increase foot traffic. Whether Chestnut Street's decline was an inevitable sign of the times, or whether the discount stores we see today were ushered in by a failed concept, we will never really know.

The concept of eliminating streets has seen success in smaller towns across the United States. In the 1980's, the college towns of Charlottesville, VA and Burlington, VT transformed major downtown thoroughfares into pedestrian malls bringing life back to stagnant retail corridors.

But it's clear that in order for large, dynamic cities to succeed, idealistically accommodating one type of traffic doesn't work. Wide roads and lots of cars scare away pedestrians, but most of those pedestrians get here in a car. Urban planning is a compromise of ideals which needs to accommodate a broad range of wants and needs. This complexity needs to be understood as the city progresses and we continue to entertain new ideas.

While we dream about pedestrianizing the waterfront and making our small streets bike-friendly, implementation will be key in these concepts succeeding. It's obvious that Interstate 95 and the Vine Street Expressway scarred the urban landscape, but no one would have guessed that a massive pedestrian oriented project would have been just as detrimental.

The story of the Transitway is not about pedestrianization killing off commerce. The slumlord Sam Rapport had far more to do with it. He held numerous properties along the block and used blight uses and outright abandonment as a tool to drive out other owners; he would then buy out their building, playing a sort of chess game where if anyone wanted to develop--they'd have to buy from him. This along with SEPTA's bizarre insistence on running buses in two directions on the street, with signal crossing mid-block, also helped make the pace miserable. Finally, the actual materials used were horrible; under the corrupt administration of the time, the brick sidewalks were half normal thickness and quickly crumbled, completing the "Escape From New York" vibe. No, it wasn't the Transitway that killed Chestnut Street -- it was corruption. mcget/trophy bikes

ReplyDelete