In what wasn't one of his ugliest projects, Carl Dranoff's 777 South Broad is finally open on South Broad Street. Anyone who has driven up South Broad over the past year might wonder, with the low quality mashed potato board construction used to erect the quasi-Deco apartment building, what really took so long? And even more importantly, what's this mid-century, Miami-esque recreation going to look like in a decade.

Perhaps Dranoff hasn't been at this game long enough to learn from his mistakes, but even after the harsh criticism he received after piecing together Symphony House, he still focuses on a laundry list of amenities rather than quality or style. To him excess is everything no matter how short its lifespan, how soon it will need to be replaced, or how cheap it may look. He builds disposable buildings.

Symphony House and 777 are urban McMansions. Before long the low quality materials used on both these buildings will be lining Broad Street's sidewalks.

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Market East Gets On Target

Who killed Market East? Well let's take a look at the big box, discount department stores that typically provide the scapegoat for the death of the American Main Street. After all, Market East is the historic model for every Main Street in North America. The answer might not be as simple as blaming Walmart.

Who killed Market East? Well let's take a look at the big box, discount department stores that typically provide the scapegoat for the death of the American Main Street. After all, Market East is the historic model for every Main Street in North America. The answer might not be as simple as blaming Walmart.First of all, Walmart didn't kill small town Main Street. That's just how activists and protesters remember it. Small town Main Street died 30 to 40 years ago, before the Walmarts and Targets were what they are today, around the same time and for the same reason big city downtowns died. Small towns started becoming sprawling, independent suburbs, with strip malls, shopping malls, all catering to the car. This is even more evident in small towns where everyone has and always has had a car, making downtowns even more useless than big city downtowns, particularly during the 60s and 70s when suburban sprawl was en vogue.

Once this cultural mindset was well established and absolutely nothing remained in these small city's downtowns, discount department stores began to grow, and these megamarts became the nail in the coffin of already dead Main Streets. The difference between, say, Scranton and Philadelphia is the fact that Philadelphia, as well as a number of major cities, managed to retain a population significant enough to warrant the retention of a practical public transportation system and walkability, which is why Targets and Walmarts haven't killed downtown Chicago, New York, Toronto, DC, etc.

It's easy to blame megamarts for killing small town business, but more fault is on the part of a lingering mid-century culture of convenience in lieu of quality. Most of the successful, post-industrial cities manage to walk a sustainable balance. And Philadelphia actually did that by using that discount element to combat suburban competition by putting it right on our Main Street.

As much as we love to hate it, anyone who's been to Market East can tell you that the big box, discount chains are the only thing keeping Market East alive. And Target aptly placed in the Disney Hole might introduce the competition needed to put products back on the shelves at K-Mart and encourage PREIT to start implementing some of these proposed changes they claim to be so excited about and actually improve our Main Street.

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

More Nightmares for Broad?

For those of you who don't remember Inga Saffron's 2007 critique of Symphony House, she basically said that Carl Dranoff took and otherwise bland Bower Lewis Thrower design and put it in drag. After his unsportsmanlike reactionary article published by the Inquirer, and several comments by Inquirer staff that Ms. Saffron had essentially castrated the man, I have been eagerly anticipating her review of the humbled man's latest incarnation: 777 South Broad, an apartment rental community with ground floor retail. Tonight's ribbon cutting, including Carl Dranoff and a "flash-mob" frazzled Mayor Nutter, will hopefully mean that we can expect her review of the apartment complex by this weekend.

For those of you who don't remember Inga Saffron's 2007 critique of Symphony House, she basically said that Carl Dranoff took and otherwise bland Bower Lewis Thrower design and put it in drag. After his unsportsmanlike reactionary article published by the Inquirer, and several comments by Inquirer staff that Ms. Saffron had essentially castrated the man, I have been eagerly anticipating her review of the humbled man's latest incarnation: 777 South Broad, an apartment rental community with ground floor retail. Tonight's ribbon cutting, including Carl Dranoff and a "flash-mob" frazzled Mayor Nutter, will hopefully mean that we can expect her review of the apartment complex by this weekend.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

Blatstein's New Empire

Blatstein's been a buzz this week in Philly's blogosphere. Most of the ink is over the typical shenanigans that make developing anything in this town as acid-inducing as trying to wrap your head around the success of Glee. There's no use going into the maniacal specifics taking place at 1400 Spring Garden short of saying it's costing both sides tens of thousands of dollars and is being held up in part by the great thorn in Philadelphia's ass, PREIT.

Blatstein's been a buzz this week in Philly's blogosphere. Most of the ink is over the typical shenanigans that make developing anything in this town as acid-inducing as trying to wrap your head around the success of Glee. There's no use going into the maniacal specifics taking place at 1400 Spring Garden short of saying it's costing both sides tens of thousands of dollars and is being held up in part by the great thorn in Philadelphia's ass, PREIT.With that said, the sale of the State Office Building to Bart Blatstein of Tower Development is moving forward, even if at a snail's pace. With the never ending success of the Piazza at Schmidt's transforming a once desolate pocket of Northern Liberties into a new city of its own, and Avenue North anchoring an element of - well, something other than a crime statistic - in North Philadelphia, Blatstein's vision for Broad and Spring Garden will be met with eager anticipation. If this corner sees a fraction of the success seen at the Piazza it could be the catalyst to bridge the gap between Center City and Temple University.

The project is purported to include apartments or condos, shopping, and possibly a high rise addition. New residential life on North Broad Street could not only bring life to the street itself but open up the insular Loft District and link Spring Garden and Fairmount to Center City, maybe even someday encouraging the redevelopment of the architectural gems along Ridge Avenue and of course the sadly neglected Divine Lorraine.

Wednesday, March 10, 2010

Replace Our History, or Create a New One?

Philadelphia - historic as it may be - has always functioned as a working city and as a result, has no inherently true "historic districts". Center City's one seemingly historic district is the result of a mid-century attempt to reconstruct a Colonial past, one which is only as important as a number of other movements responsible for the PSFS Building, the Divine Lorraine, even the Cira Centre. The result, Society Hill's "historic district", is a collage of questionable reconstructions which sacrificed dozens of 18th and 19th century buildings, some by Willis Hale and Frank Furness. This attempt at architectural cohesiveness created a very peaceful, historic illusion, but compared to the rest of Center City is one of the less interesting neighborhoods to look at.

Historic districts are important but it is just as important to respect the existing history of a neighborhood which has naturally evolved. The Keystone National Bank Building is a prime example. Is it more historically respectful to replicate the original facade which was replaced less than ten years after it was constructed, or do you pay homage to the five successive facades implemented over the following 100 years by designing something truly modern that represents the needs of the existing urban fabric of a culturally, historically, and architecturally diverse neighborhood? Unfortunately we usually fall somewhere in the middle, attempting to appease the devout advocates as well as the needs of the client, and we end up with bland, historic interpretations. Instead we should be replacing the avante garde masterpieces we've lost over the decades with exciting new architecture.

An empty construction site or blank facade has the potential to be architecturally significant someday. In a city as aesthetically diverse as Philadelphia, architects should be creating tomorrow's history and not wasting their time recreating yesterday's.

Historic districts are important but it is just as important to respect the existing history of a neighborhood which has naturally evolved. The Keystone National Bank Building is a prime example. Is it more historically respectful to replicate the original facade which was replaced less than ten years after it was constructed, or do you pay homage to the five successive facades implemented over the following 100 years by designing something truly modern that represents the needs of the existing urban fabric of a culturally, historically, and architecturally diverse neighborhood? Unfortunately we usually fall somewhere in the middle, attempting to appease the devout advocates as well as the needs of the client, and we end up with bland, historic interpretations. Instead we should be replacing the avante garde masterpieces we've lost over the decades with exciting new architecture.

An empty construction site or blank facade has the potential to be architecturally significant someday. In a city as aesthetically diverse as Philadelphia, architects should be creating tomorrow's history and not wasting their time recreating yesterday's.

Tuesday, March 2, 2010

Hale's Legacy

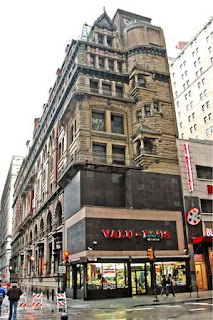

Willis Hale's legacy in Philadelphia is often as macabre as his architecture. With the eerie Divine Lorraine, once home to the International Peace Movement Mission and Father Divine's followers, vacantly awaiting a new owner after being stripped of it's soul and left behind by an absent European investor, and the Keystone Bank Building's upper floors of the former Drucker's Bellevue Health Baths on Chestnut and Juniper quickly decaying above the retro-fitted Value Plus facade.

Willis Hale's legacy in Philadelphia is often as macabre as his architecture. With the eerie Divine Lorraine, once home to the International Peace Movement Mission and Father Divine's followers, vacantly awaiting a new owner after being stripped of it's soul and left behind by an absent European investor, and the Keystone Bank Building's upper floors of the former Drucker's Bellevue Health Baths on Chestnut and Juniper quickly decaying above the retro-fitted Value Plus facade. Unfortunately most of Hale's neo-Gothic Victorian examples were razed in the mid-century quest to return Philadelphia to its Colonial roots. These two in particular, arguably his most well known works, share a distinctly Halian identity.

Unfortunately most of Hale's neo-Gothic Victorian examples were razed in the mid-century quest to return Philadelphia to its Colonial roots. These two in particular, arguably his most well known works, share a distinctly Halian identity. Developer Alon Barzilay and architects JKR Partners have been in a debate with the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia on a rendering of what will be the latest of six interpretations of it's lower facade in the building's 123 year history. While Barzilay intends to fully restore the existing, historic masonry, the PAGP is concerned with JKR's interpretation of the 1960's addition. I just hope the roof survives the PAGP's stubbornness.

Developer Alon Barzilay and architects JKR Partners have been in a debate with the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia on a rendering of what will be the latest of six interpretations of it's lower facade in the building's 123 year history. While Barzilay intends to fully restore the existing, historic masonry, the PAGP is concerned with JKR's interpretation of the 1960's addition. I just hope the roof survives the PAGP's stubbornness. The numerous facades of the Keystone Bank Building - also known as the Lucas Building and the Hale Building - throughout its 123 year history. Seen here in 1893, 1900, 1930, 1955, 1970, Today, and JKR's rendering.

The numerous facades of the Keystone Bank Building - also known as the Lucas Building and the Hale Building - throughout its 123 year history. Seen here in 1893, 1900, 1930, 1955, 1970, Today, and JKR's rendering.Everything and nothing is historic about the facade. It would only be fitting for its latest incarnation to be specifically dated to modern, 21st century architecture. Unless Barzilay plans to alter the remaining original details, any historical organization has no business dictating design. The PAGP can and should be offering suggestions, but it is not their place to halt progress based on the replacement of an insignificant facade. Their area of expertise is in existing, historical structures, not design, and they seem to have successfully hijacked an absolute authority over this building that they have no business exercising.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)